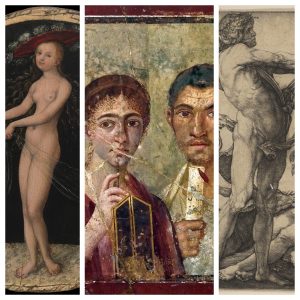

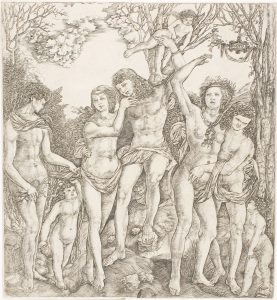

( manuscript dealing with sexuality and relationships, weaving together “cases, stories and myths )

Preface

The erotic instinct is something questionable, and will always be so no matter what human laws are made about it. It belongs on the one hand, to our original animal nature, which will exist as long as we have an animal body. On the other hand, it is connected with the highest forms of spirit. But it blooms only when spirit and instinct are in harmony. —CARL JUNG

I say that male and female are cast in the same mould: save for education and custom the difference between them is not great. In The Republic Plato summons both men and women indifferently to a community of all studies, administrations, offices and vocations both in peace and war; and Antisthenes the philosopher removed any distinction between their virtue and our own. Montaigne

If you look closely at an M.C. Escher print, you see confusion. Each element makes sense, but not together. And everyone seems calm. But, looking on, you want to ask, “Don’t these people see that they are living in an impossible world”? At any moment someone may fall on their head or vanish into a space that cannot exist. However, they continue to play music or doze. And one supposes that even when someone turns a corner and vanishes entirely, the rest do not glance up.

But we too live in impossible worlds; with our minds wanting opposite things, our souls on vacation, and our bodies taking in information that they don’t tell us about (or at least we don’t listen).

Like the men in Escher’s print, we walk about pretending that nothing unusual is happening. And then comes a sudden eruption of the impossible and absurd. We find out that our mild, seventy five year old neighbor has run off with the church secretary, or a colleague has embezzled a million dollars and spent it on prostitutes and hashish. Or perhaps you find yourself obsessing about some young woman who serves coffee, and has the loveliest bosom. And you say “What is this about?” You don’t even know her.

We are strange and composite. One suspects that we were designed by some kind of committee of angels, well intentioned, but compromising, and rushed to get the job done.

There is no stronger proof or demonstration of this puzzling, impossible nature than our erotic life. Time and again, people do things that defy logic and experience. Women stay with men who drink and abuse them. Middle aged men take up with women younger than their daughters, abandoning family and career to walk about in sandals, with dyed hair on faraway beaches. Can there be any doubt about where that will end? Why not just hurl yourself off a building? It would be less painful.

The Greeks saw love as a kind of madness. They were right and wrong; both at the same time. They were right that we do impossible things when we feel erotic emotion. But what they missed is that the impossibility was there all along. As in the Escher print, each little corner of our lives seems perfectly normal. But if you look closely the illogic and impossibility is dyed through. Now and then there is a turning which makes your mind reel.

Human emotion is like what the philosopher Wittgenstein called a city that has no map; something that cannot be known “from above;” only discovered by patiently walking through this way and that over and over. (He was, of course, not talking about places you find in an atlas).

Of emotions, particularly our erotic lives whatever you can say is false is also true. For some, a lover may be a still point, a center. All of the bends and turns of the impossible world lead to her. Dante wrote of this and how Beatrice saved his life. One may ask, when we are not under the spell of his Commedia (or our own loves), how can this be? How can this one or that, a human female (or male), like oneself, lead to anything other than a roll in the hay. How does one get from the shapely figure, the sparkling eye, to God? Dante’s poem still moves us. And some will say they have experienced something like it. But if you try to map it upon what you know of the world it makes no sense.

How is it possible that as I get older, I know less and even the familiar becomes strange? I used to think I knew what love was, and what the world contained. But my experience does not fit my ideas. Here I am, in my sixties: I should begin packing for the journey to the other side, but nothing fits. Whatever ideas I want to pack, hang over the edges and the lid won’t close.

For instance, I realized one day what a curious thing it was that after 40 years, I was very much in love with my wife. It is not a matter of companionability, or comfort. We are in love. It is not supposed to happen. Yet, there is still the longing, sometimes sharp and sudden, in the middle of the day. There is still the sense of absurd good fortune.

At times I feel like a little child who has stolen an extra dessert from God’s table, and She had not noticed. -I sit in the shadow of a big oak tree, savoring what I have stolen and wondering how I got away with it. Then the Grand Lady strolls out from between the trees, and smiles, saying, “What a fine weather we are having.”

As a psychologist I know about habit and boredom. Whatever is repeated loses interest. Whatever one possesses becomes background to new and shifting desires. Couples become companionable over time and there are studies to prove it.

Yes, it is said that either desire fades and is put aside, or it becomes an addiction, needing more and desperate measures to produce less effect. Psychologically speaking the legend of Don Juan (who you will meet later in this book) is an absurd wish-fulfilling dream. In real life, long before the total of conquests reaches “1005” the seducer is desperately trying to escape boredom and despair.

Reflecting on these things has been like opening a basement door in a house where I have lived for years, expecting to find a room of no particular interest; yet I find that door opens into a plaza where there is a bazaar in a city both familiar and strange; a place of exotic spices and perfumes. There is an intense azure sky, which recalls the endless summers of boyhood. How could there be such a place?

There seems to be a mystery to love connected, as Dante would have it, to that ‘which moves the sun and other stars.’

It is absurd. Yet it seems to be true.

In this book I will explore five themes which seem to create the contradictory spaces in which love is enacted

These themes are: 1) The delusions of gender; 2) Our discomfort in being embodied, and “thrown into life.” 3) Our desire to remain fixed within ourselves while yet feeling imprisoned in that self. 4) The mystery of how passion can vanish, reappear, and sometimes renew itself. 5) The vulnerability of love and the fear it evokes.

- Gender: Our erotic lives are complicated and often spoiled by the belief that there is an essential difference between men and women. When we believe that we are defined by gender, rather than fundamentally human, relationships become opaque. For many men loving a woman is like keeping a cat. The feline and the feminine mind are unknowable, making deep emotional connection difficult and sometimes impossible.

- The puzzle of the body: We are puzzled by the way in which our minds live through bodies. Some ancient philosophers believed that we can never feel completely at home in our own skin because we are spirits descended from the stars, and “thrown into life.” And while much of the time we are not aware of the seams and liminal zones of embodied life, sexual desire powerfully evokes it. In most languages the thing we do with the one we love is also a swear word.

- Narcissism : We want to be entirely for our self, in our self. Yet at the same time we feel confined by that selfhood. We want to be a fortress defended against all demands, and yet escape isolation and imprisonment within that fortress. Though we might long to escape the endless, futile struggle to wrest the satisfaction of our desires from the world, we fear opening our hearts.

- Love fades. Whether chocolate cake or kisses, whatever you experience again and again begins to fade. And yet, sometimes love seems able to renew itself. How is that done? Can you be “in love” with a partner in the same way that some aging artists continue to be delighted by their art? How do they do that?

- We possess nothing: When you choose to love, you double your bet against loss and disappointment. It is hard enough to endure the uncertainty of our own lives, but when you love someone you double the ways in which you can be harmed: your lover may get sick, she may die, or she may decide she no longer loves you. How can we live with this? One might ask, ‘why don’t more people live alone and keep a cat’ (and, of course, some do).